Introduction:

Electric circuit theory and electromagnetic theory are the two fundamental theories upon which all branches of electrical engineering are built. Many branches of electrical engineering, such as power, electric machines, control, electronics, communications, and instrumentation, are based on electric circuit theory. Therefore, the basic electric circuit theory knowledge is the most important course for an electrical engineer, and always an excellent starting point for a beginning student in electrical engineering education.

In electrical engineering, we are often interested in communicating or transferring energy from one point to another. To do this requires an interconnection of electrical devices. Such interconnection is referred to as an electric circuit, and each component of the circuit is known as an element.

Analyzing a circuit, means studying the behavior of the circuit: How does it respond to a given input? How do the interconnected elements and devices in the circuit interact?

Units and Scales:

In order to state the value of some measurable quantity, we must give both a number and a unit, such as “3 meters.” Fortunately, we all use the same number system. This is not true for units, and a little time must be spent in becoming familiar with a suitable system.

The most frequently used system of units is the one adopted by the National Bureau of Standards in 1964; it is used by all major professional engineering societies and is the language in which today’s textbooks are written. This is the International System of Units (abbreviated SI in all languages), adopted by the General Conference on Weights and Measures in 1960.

The SI is built upon seven basic units: the meter, kilogram, second, ampere, kelvin, mole, and candela (see Table1). This is a “metric system,” Units for other quantities such as volume, force, energy, etc., are derived from these seven base units.

| Base Quantity | Name | Symbol |

| Length | Meter | m |

| Mass | Kilogram | kg |

| Time | Second | s |

| Electric current | Ampere | A |

| Thermodynamic temperature | Kelvin | K |

| Amount of substance | Mole | mol |

| Luminous intensity | Candela | Cd |

Table 1

The SI uses the decimal system to relate larger and smaller units to the basic unit, and employs prefixes to signify the various powers of 10. A list of prefixes and their symbols is given in Table 2.

| Factor | Name | Symbol | Factor | Name | Symbol |

| 10-24 | yocto | y | 1024 | yotta | Y |

| 10-21 | zepto | z | 1021 | zetta | Z |

| 10-18 | atto | a | 1018 | exa | E |

| 10-15 | femto | f | 1015 | peta | P |

| 10-12 | pico | p | 1012 | tera | T |

| 10-9 | nano | n | 109 | giga | G |

| 10-6 | micro | µ | 106 | mega | M |

| 10-3 | milli | m | 103 | kilo | k |

| 10-2 | centi | c | 102 | hector | h |

| 10-1 | deci | d | 101 | deka | da |

Table 2

Charge and Current:

The concept of electric charge is the underlying principle for explaining all electrical phenomena. Also, the most basic quantity in an electric circuit is the electric charge. We all experience the effect of electric charge when we try to remove our wool sweater and have it stick to our body or walk across a carpet and receive a shock.

Charge is an electrical property of the atomic particles of which matter consists, measured in coulombs (C).

We know from elementary physics that all matter is made of fundamental building blocks known as atoms and that each atom consists of electrons, protons, and neutrons.

The charge e of an electron is: e = -1.602 ×10-19C

The charge e of a proton is: e = +1.602 ×10-19C

And neutron is chargeless however if we break it, it gives us an electron and a proton.

The following points should be noted about electric charge:

- According to experimental observations, the only charges that occur in nature are integral multiples of the electronic charge e = -1.602 × 10-19 C so the amount of charge we can find in nature must be a multiplication of an integer n and e, furthermore, it’s is usually represented by Q or q so we have q = n⸳e which is measured in Coulombs (C).

- The coulomb is a large unit for charges. In 1 C of charge, there are 1 ∕ (1.602 × 10-19) = 6.24 × 10+18 Thus, realistic or laboratory values of charges are on the order of pC, nC, or μC.

- The law of conservation of charge states that charge can neither be created nor destroyed, only transferred. Thus, the algebraic sum of the electric charges in a system does not change.

A quantity of charge that does not change with time is typically represented by Q. The instantaneous amount of charge (which may or may not be time-invariant) is commonly represented by q(t), or simply q.

This convention is used by many of the texts and books: capital letters are reserved for constant (time-invariant) quantities, whereas lowercase letters represent the more general case. Thus, a constant charge may be represented by either Q or q, but an amount of charge that changes over time must be represented by the lowercase letter q.

A unique feature of electric charge or electricity is the fact that it is mobile; that is, it can be transferred from one place to another, where it can be converted to another form of energy.

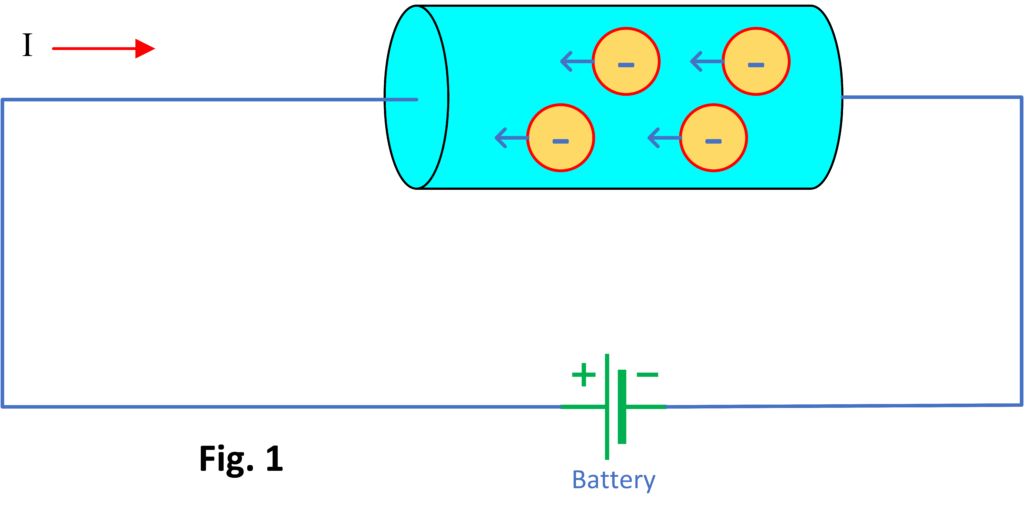

When a conducting wire (consisting of several atoms) is connected to a battery (a source of electromotive force), the charges are compelled to move; positive charges move in one direction while negative charges move in the opposite direction. This motion of charges creates electric current. It is conventional to take the current flow as the movement of positive charges. That is, opposite to the flow of negative charges, as Fig. 1 illustrates.

Although we know that current in metallic conductors is due to negatively charged electrons, however, in ionized gases, in electrolytic solutions, and in some semiconductor materials, positive charges in motion constitute part or all of the current. We will follow the universally accepted convention that current is the net flow of positive charges.

As we said earlier, if we somehow create a situation to move charges, for example by wires and batteries, the phenomenon of “charge in motion” occurs, which is called electric current. So electric current is simply the motion of charges in a specified direction inside a wire or anything that can conduct them towards their way from negative side to the positive side of the electromotive force.

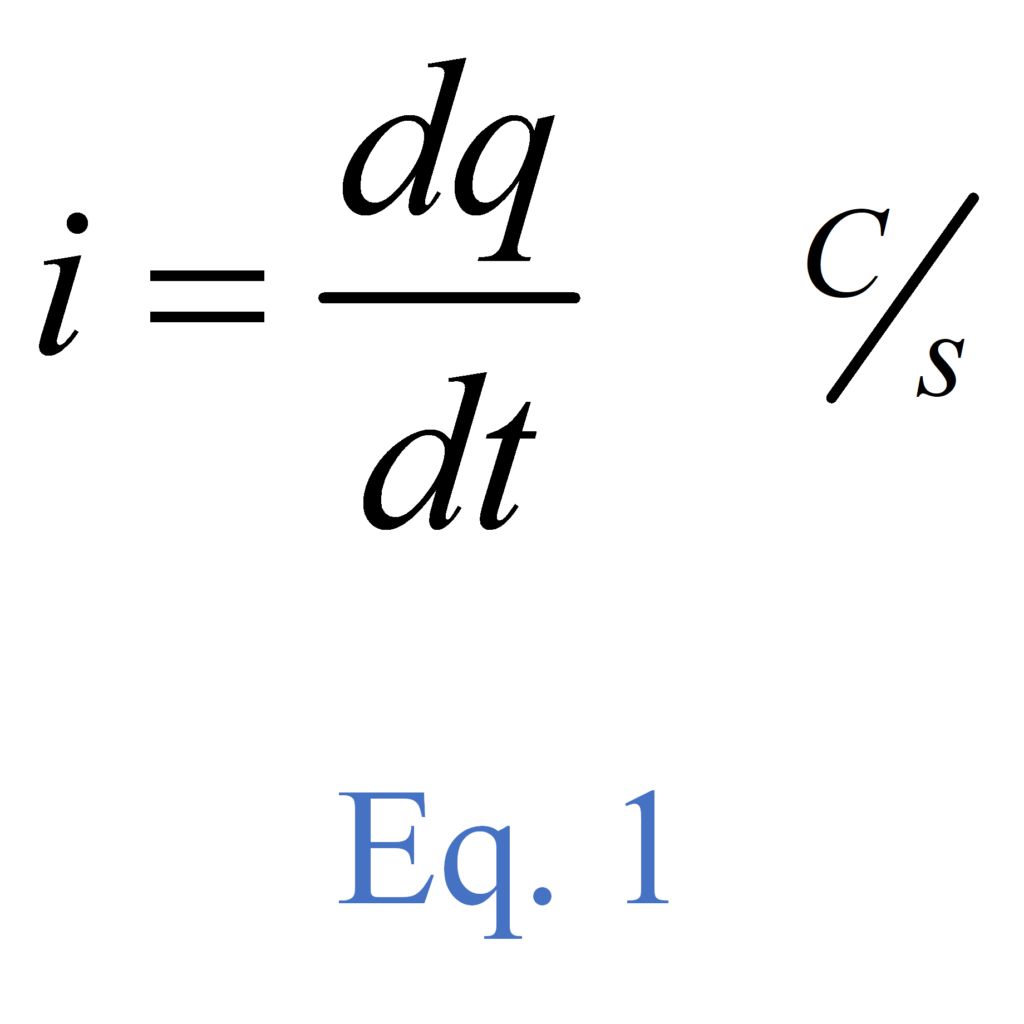

Electric current is the time rate of change/motion of charge, measured in amperes (A). Mathematically, the relationship between current i, charge q, and time t is:

1 Ampere = 1 coulomb / second

Also, the charge transferred between time t0 and t is obtained by integrating both sides of Eq.1, by doing that we obtain equation 2:

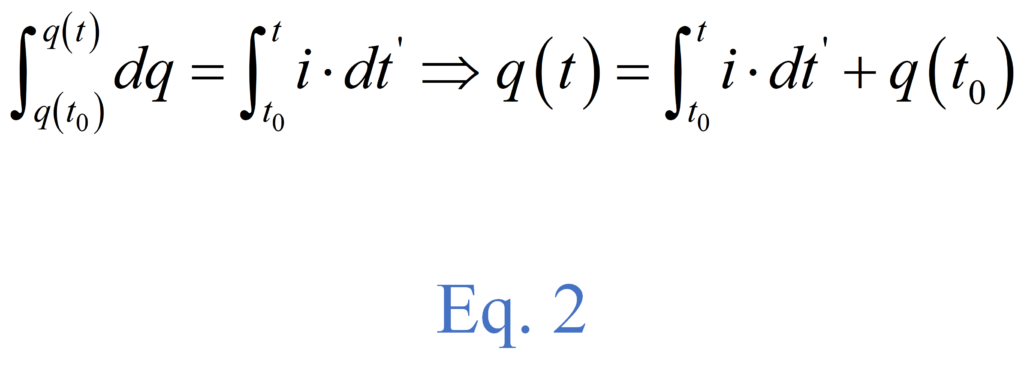

Several different types of current are illustrated in Fig. 2:

A current that is constant in time is called a direct current, or simply DC. We will find many practical examples of currents that vary sinusoidally with time; currents of this form are present in normal household circuits. Such a current is often referred to as alternating current, or AC. Exponential currents and damped sinusoidal currents will also be encountered later.

By convention, we will use the symbol I to represent a constant current. If the current varies with respect to time (either dc or ac) we will use the symbol i.

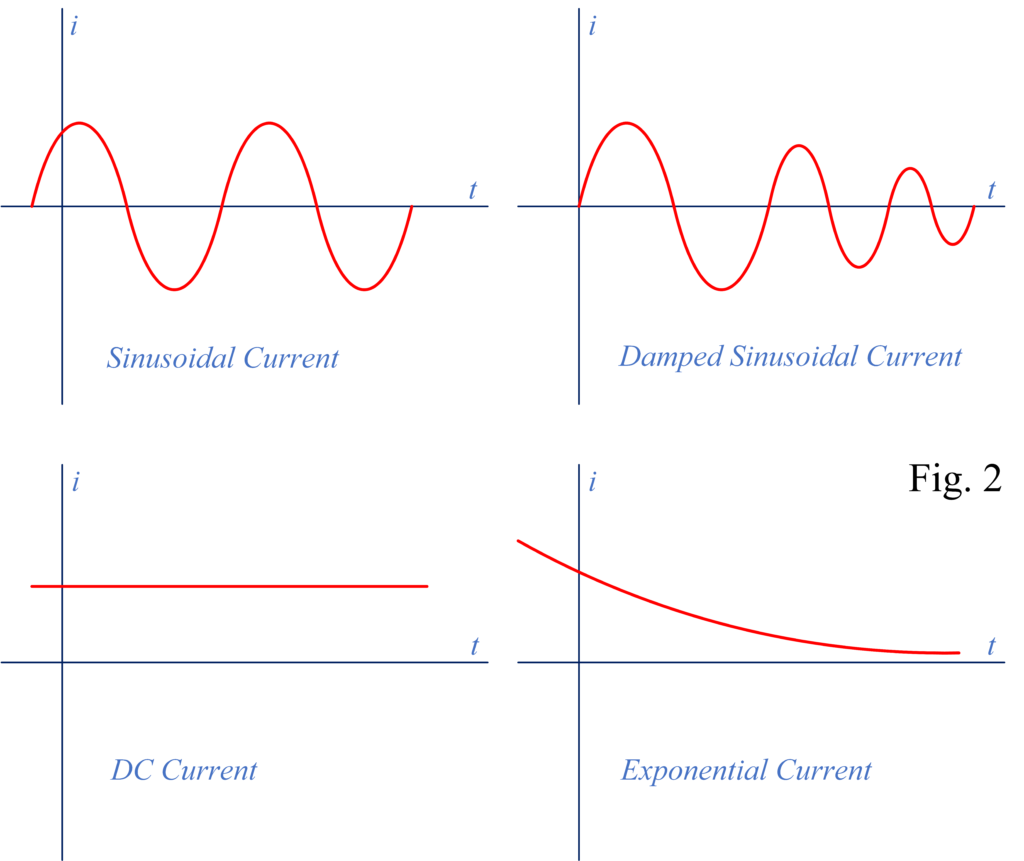

We create a graphical symbol for current by placing an arrow next to the conductor. Thus, in Fig. 3, the direction of the arrow and the value +3 A indicate either that a net positive charge of +3 C/s is moving to the right or that a net negative charge of -3 C/s is moving to the left each second.

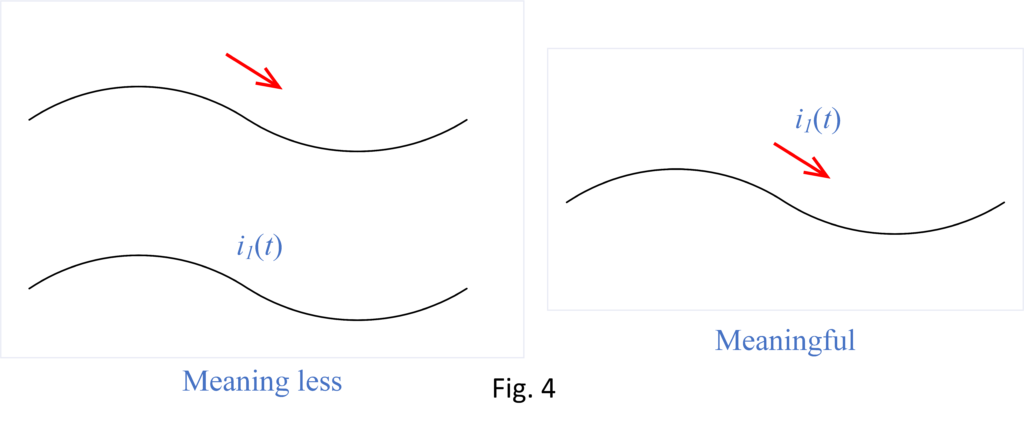

It is essential that we realize that the current arrow does not indicate the “actual” direction of current flow but is simply part of a convention that allows us to talk about “the current in the wire” in an unambiguous manner. The arrow is a fundamental part of the definition of a current! Thus, to talk about the value of a current i1(t) without specifying the arrow is to discuss an undefined entity. Take a look at figure 4.

Voltage:

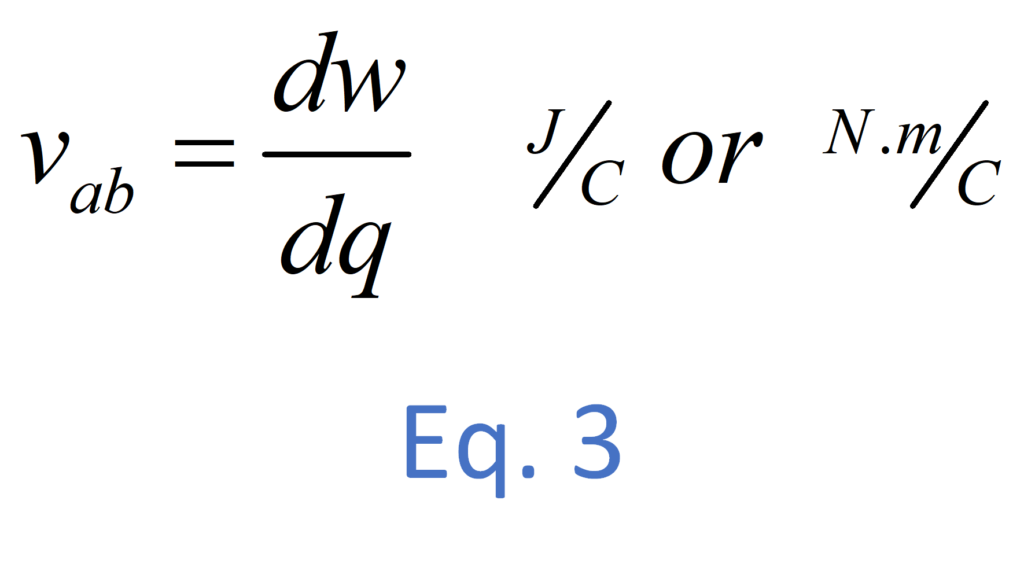

As explained briefly in the previous section, to move the electron in a conductor in a particular direction requires some work or energy transfer. This work is performed by an external electromotive force (emf), typically represented by the battery in Fig. 1. This emf is also known as voltage or potential difference. The voltage vab between two points a and b in an electric circuit is the energy (or work) needed to move a unit charge from b to a; mathematically:

1 volt = 1 joule/coulomb = 1 newton-meter/coulomb

Voltage (or potential difference) is the energy required to move a unit charge from a reference point (-) to another point (+), measured in volts (V).

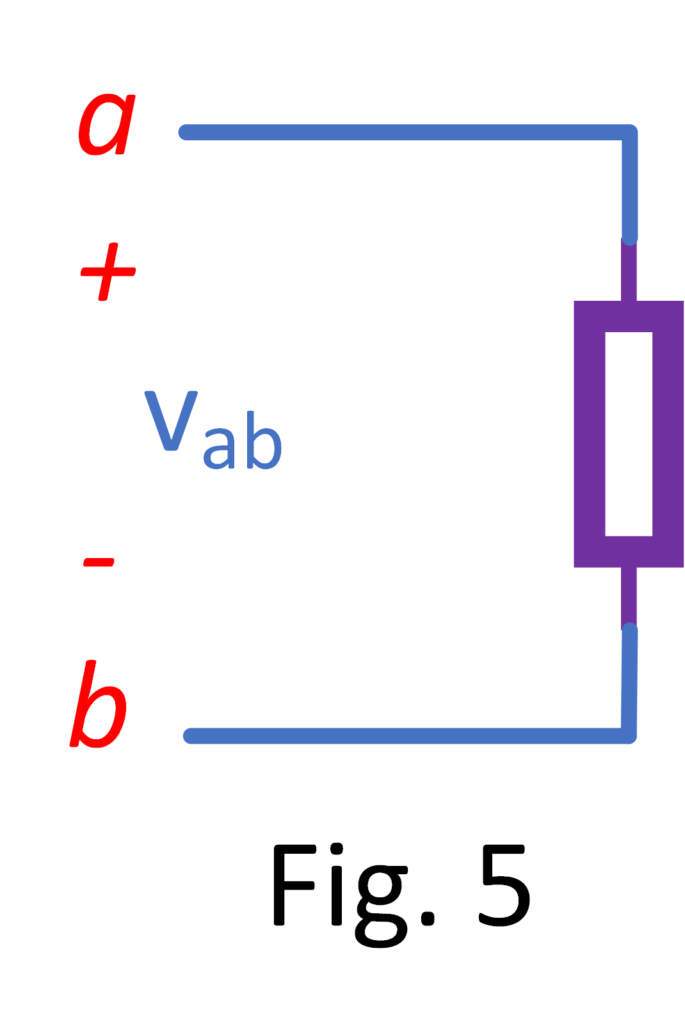

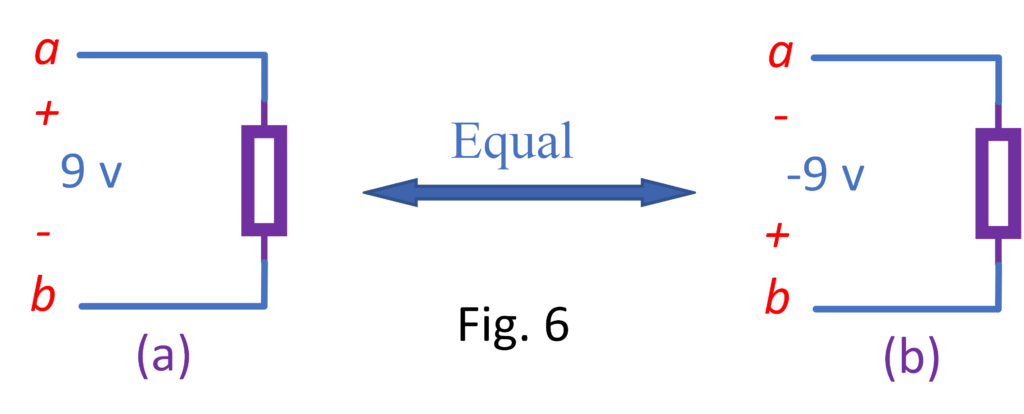

Figure 5 shows the voltage across an element (represented by a rectangular block) connected to points a and b. The plus (+) and minus (-) signs are used to define reference direction or voltage polarity. The vab can be interpreted in two ways: (1) Point a is at a potential of vab volts higher than point b, or (2) the potential at point a with respect to point b is vab. It follows logically that in general:

vab = -vba

For example, in Fig. 6, we have two representations of the same voltage. In Fig. 6(a), point a is +9 V above point b; in Fig. 6(b), point b is -9 V above point a. We may say that in Fig. 6(a), there is a 9-V voltage drop from a to b or equivalently a 9-V voltage rise from b to a. In other words, a voltage drop from a to b is equivalent to a voltage rise from b to a.

Like electric current, a constant voltage is called a dc voltage and is represented by V, whereas a sinusoidally time-varying voltage is called an ac voltage and is represented by v. A dc voltage is commonly produced by a battery; ac voltage is produced by an electric generator.

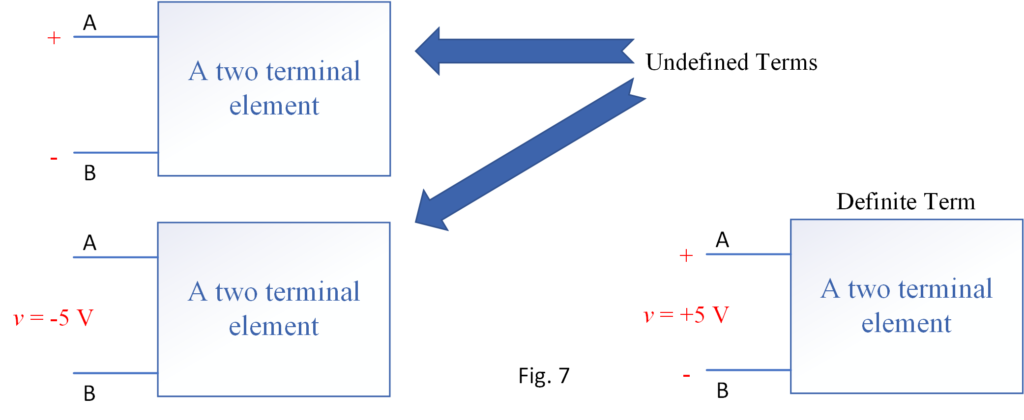

Just as we noted in our definition of current, it is essential to realize that the plus-minus pair of algebraic signs does not indicate the “actual” polarity of the voltage but is simply part of a convention that enables us to talk unambiguously about “the voltage across the terminal pair.” The definition of any voltage must include a plus-minus sign pair! Using a quantity v1(t) without specifying the location of the plus-minus sign pair is using an undefined term. Figure 5 indicates some undefined cases comparing them to the definite term.

Power and Energy

Although current and voltage are the two basic variables in an electric circuit, they are not sufficient by themselves. For practical purposes, we need to know how much power an electric device can handle.

We also know that when we pay our bills to the electric utility companies, we are paying for the electric energy consumed over a certain period of time. Thus, power and energy calculations are important in circuit analysis.

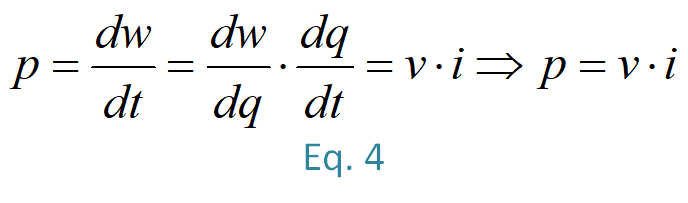

To relate power and energy to voltage and current, we recall from physics that:

Power is the time rate of expending or absorbing energy, measured in watts (W).

We write this relationship as:

where p is power in watts (W), w is energy in joules (J), and t is time in seconds (s).

The power absorbed or supplied by an element is the product of the voltage across the element and the current through it. If the power has a (+) sign, power is being delivered to or absorbed by the element. If, on the other hand, the power has a (-) sign, power is being supplied by the element.

But how do we know when the power has a negative or a positive sign?

Current direction and voltage polarity play a major role in determining the sign of power. It is therefore important that we pay attention to the relationship between current i and voltage v in Fig. 8.

The voltage polarity and current direction must conform with those shown in Fig. 8(a) in order for the power to have a positive sign. This is known as the passive sign convention. By the passive sign convention, current enters through the positive polarity of the voltage. In this case, p = +vi or vi > 0 implies that the element is absorbing power. However, if current leaves the positive sign of voltage, then the power will be p = –vi or vi < 0, as in Fig. 8 (b), the element is releasing or supplying power.

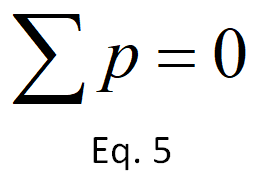

In general, the power supplied in a circuit must be equal to the power absorbed by the circuit. In fact, the law of conservation of energy must be obeyed in any electric circuit. For this reason, the algebraic sum of power in a circuit, at any instant of time, must be zero:

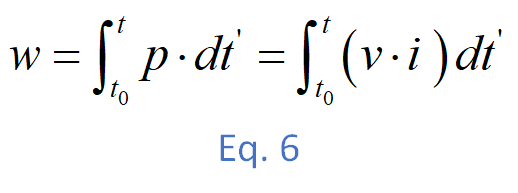

From Eq. 4, the energy absorbed or supplied by an element from time t0 to time t is shown in equation 6:

Energy is the capacity to do work, measured in joules (J).